Public bathing

Public baths originated when most people in population centers did not have access to private bathing facilities. Though termed "public", they have often been restricted according to gender, religious affiliation, personal membership, and other criteria.

In addition to their hygienic function, public baths have also been social meeting places. They have included saunas, massages, and other relaxation therapies, as are found in contemporary day spas.

As the percentage of dwellings containing private bathrooms has increased in some societies, the need for public baths has diminished, and they are now almost exclusively used recreationally.

History

[edit]Indus Valley Civilization

[edit]

Some of the earliest public baths are found in the ruins in of the Indus Valley civilization. According to John Keay, the "Great Bath" of Mohenjo Daro in present-day Pakistan was the size of 'a modest municipal swimming pool', complete with stairs leading down to the water at each one of its ends.[1]

The bath is housed inside a larger—more elaborate—building and was used for public bathing.[1] The Great Bath and the house of the priest suggest that the Indus had a religion.

Ancient Greece

[edit]In Greece by the sixth century BC, men and women washed in basins near places of physical and intellectual exercise. Later gymnasia had indoor basins set overhead, the open maws of marble lions offering showers, and circular pools with tiers of steps for lounging.

Bathing was ritualized, and becoming an art, with cleansing sands, hot water, hot air in dark vaulted "vapor baths", a cooling plunge, and a rubdown with aromatic oils. Cities all over Ancient Greece honored sites where "young ephebes stood and splashed water over their bodies".

Greek public bathing spread to the already rich ancient Egyptian bathing culture, during Ptolemaic rule[2][3] and ancient Rome.

China

[edit]Bathing culture in Chinese literature can be traced back to the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE), where Oracle bone inscriptions describe the people washing hair and body in bath, suggesting people paid attention to personal hygiene. Book of Rites, a work regarding Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE) ritual, politics, and culture compiled during the Warring States period, describes that people should take a hot shower every five days and wash their hair every three days. It was also considered good manners to take a bath provided by the host before the dinner. In the Han dynasty, bathing became a regular activity every five days.[4]

Ancient public bath facilities have been found in ancient Chinese cities, such as the Dongzhouyang archaeological site in Henan Province. Bathrooms were called Bi (Chinese: 湢), and bathtubs were made of bronze or timber.[5] Bath beans, a powdery soap mixture of ground beans, cloves, eaglewood, flowers, and even powdered jade, was a luxury toiletry in the Han dynasty; commoners used powdered beans without spices. Luxurious bathhouses built around hot springs were recorded in the Tang dynasty.[4] While royal bathhouses and bathrooms were common among ancient Chinese nobles and commoners, the public bathhouse was a relatively late development. In the Song dynasty (960–1279), public bathhouses became popular and ubiquitous,[5] and bathing became an essential part of social life and recreation. Bathhouses often provided massage, manicure, rubdowns, ear cleaning, food and beverages.[5] Marco Polo, who traveled to China during the Yuan dynasty, noted Chinese bathhouses used coal for heating, which he had never seen in Europe.[6] At that time coal was so plentiful that Chinese people of every social class took frequent baths, either in public baths or in bathrooms in their own homes.[7][8][better source needed]

A typical Ming dynasty bathhouse had slabbed floors and brick dome ceilings. A huge boiler was installed in the back of the house, connected with the bathing pool through a tunnel. Water could be pumped into the pool by water wheels attended by staff.[5]

South Korea

[edit]Unlike traditional public baths in other countries, public baths in Korea are known for having various amenities on site besides the basic bathing. This can range from public saunas known as Hanjeungmak, hot tubs, showers, and even massage tables where people can get massage scrubs.[9] Due to the popularity of Korean jjimjilbangs, some have started to open up outside of Korea.

Nepal

[edit]From at least as early as 550 AD there have been public drinking fountains in Nepal, also called dhunge dhara or hiti. The primary function of these dhunge dharas was to provide easily accessible and safe drinking water. Depending on their size and location, they were also used as a public bath and for other washing and cleaning activities. Many of them are still being used as such today.[10][11]

Japan

[edit]The origin of Japanese bathing is misogi, ritual purification with water.[12] After Japan imported Buddhist culture, many temples had saunas, which were available for anyone to use for free.

In the Heian period, houses of prominent families, such as the families of court nobles or samurai, had baths. The bath had lost its religious significance and instead became leisure. Misogi became gyōzui, to bathe in a shallow wooden tub.[13]

In the 17th century, the first European visitors to Japan recorded the habit of daily baths in sexually mixed groups.[12] Before the mid-19th century, when Western influence increased, nude communal bathing for men, women, and children at the local unisex public bath, or sentō, was a daily fact of life.

In contemporary times, many, but not all administrative regions forbid nude mixed gender public baths, with exceptions for children under a certain age when accompanied by parents. Public baths using water from onsen (hot springs) are particularly popular. Towns with hot springs are destination resorts, which are visited daily by the locals and people from other, neighboring towns.

Indonesia

[edit]

Traditionally in Indonesia, bathing is almost always "public", in the sense that people converge at riverbanks, pools, or water springs for bathing or laundering. However, some sections of riverbanks are segregated by gender. Nude bathing is quite uncommon; many people still use kain jarik (usually batik clothes or sarong) wrapped around their bodies to cover their genitals. More modest bathing springs might use woven bamboo partitions for privacy, still a common practice in villages and rural areas.

The 8th-century complex of Ratu Boko contains a petirtaan or bathing-pool structure enclosed in a walled compound.[14] This suggests that other than bathing in riverbanks or springs, people of ancient Java's Mataram Kingdom developed a bathing pool, although it was not actually "public" since it was believed to be reserved for royalty or people residing in the compound. The 14th-century Majapahit city of Trowulan had several bathing structures, including the Candi Tikus bathing pool, believed to be a royal bathing pool; and the Segaran reservoir, a large public pool.[15]

The Hindu-majority island of Bali contains several public bathing pools—some, such as Goa Gajah, dating from the 9th century. A notable public bathing pool is Tirta Empul, which is primarily used for the Balinese Hinduism cleansing ritual rather than for sanitation or recreation.[16] Its bubbling water is the main source of the Pakerisan River.

Roman Empire

[edit]

The first public thermae of 19 BC had a rotunda 25 metres across, circled by small rooms, set in a park with an artificial river and pool. By AD 300 the Baths of Diocletian would cover 140,000 square metres (1,500,000 sq ft), its soaring granite and porphyry sheltering 3,000 bathers a day. Most Roman homes, except for those of the most elite, did not have any sort of bathing area, so people from various classes of Roman society would convene at the public baths.[17] Roman baths became "something like a cross between an aqua centre and a theme park", with pools, exercise spaces, game rooms, gardens, even libraries, and theatres. One of the most famous public bath sites is Aquae Sulis in Bath, England.

Dr. Garrett G Fagan, a professor at Pennsylvania State University, described public bathing as a "social event" for the Romans in his book Bathing in Public in the Roman World. He also states that "In Western Europe only the Finns still practice a truly public bathing habit."[18][19]

Muslim world

[edit]

Public bathhouses were a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world which was inherited from the model of the Roman thermae.[20][21][22] Muslim bathhouses, also called hammams (from Arabic: حمّام, romanized: ḥammām) or "Turkish baths" (mainly by westerners due to the bath's association with the Ottoman Empire), are historically found across the Middle East, North Africa, al-Andalus (Islamic Spain and Portugal), Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and in central and eastern Europe under Ottoman rule. In Islamic culture the significance of the hammam was both religious and civic: it provided for the needs of ritual ablutions (wudu and ghusl) but also provided general hygiene and served other functions in the community such as meeting places for socialization for both men and women.[20][21][23] Archaeological remains attest to the existence of bathhouses in the Islamic world as early as the Umayyad period (7th–8th centuries) and their importance has persisted up to modern times.[23][20] Their architecture evolved from the layout of Roman and Greek bathhouses and featured a similar sequence of rooms: an undressing room, a cold room, a warm room, and a hot room. Heat is produced by furnaces which provide hot water and steam, as well as smoke and hot air passing through conduits under the floor.[21][23][22] The process of visiting a hammam was similar to that of Roman bathing, albeit with some exceptions such as the absence of exercise.[24][20]

In Judaism

[edit]

Public baths in Judaism, unlike the ritual bath (mikveh) which is used for purification after defilement, are used only for enhancing bodily cleanliness and for pleasure and relaxation. On Tisha B'Av, the fast day marking the commemoration of the Second Temple's destruction, Jews are not permitted to visit the public bath house.[25]

In the Minor tractate Kallah Rabbati (chapter 10), the early Sages of Israel instructed on what should be the conduct of every Jew who enters a public bath. Before a Jew enters a public bath, he is first required to offer a short prayer unto God, requesting that no offensive act befall him there.[26] He is also instructed on which clothes he is to remove before entering the bath itself, with the item that puts his body at the most exposure being the very last thing removed.[26] When entering a public bath, a Jew is not permitted to greet his neighbor with a verbal salutation, and if another person should greet him audibly, he is to retort: "This is a bath house."[26] Once inside, he is forbidden to sit in a fetal position upon the marble floor, such as one who puts his head between his own legs while sitting upright (others explain the sense as exercising the body);[26] nor is he permitted to rub or scratch another person's limbs with his bare hands, but may use an extended device to scratch another bather's back.[26] Furthermore, he is not permitted to have his "limbs broken" (a kind of stretching of the muscles, or massaging) while lying on the marble floor in the bath house.[26][27] These strictures were enacted in order to discourage developing any close bond and connection with another bather that might, otherwise, lead to inappropriate behavior while both men are naked. In addition, bathing with one's biological father, with one's sister's husband (brother-in-law) and with one's rabbi are all prohibited.[28]

Christian world

[edit]

Despite the denunciation of the mixed bathing style of Roman pools by early Christian clergy, as well as the pagan custom of women bathing naked in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing,[29] which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the Church Father, Clement of Alexandria. The Church built public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near monasteries and pilgrimage sites; also, the popes situated baths within church basilicas and monasteries since the early Middle Ages.[30] Pope Gregory the Great urged his followers on the value of bathing as a bodily need.[31]

Great bathhouses were built in Byzantine centers such as Constantinople and Antioch,[32][33]: 87 and the popes allocated to the Romans bathing through diaconia, or private Lateran baths, or even a myriad of monastic bath houses functioning in eighth and ninth centuries.[31] The popes maintained their baths in their residences which described by scholar Paolo Squatriti as " luxurious baths", and bath houses including hot baths incorporated into Christian Church buildings or those of monasteries, which known as "charity baths" because they served both the clerics and needy poor people.[34] Public bathing were common in mediaeval Christendom larger towns and cities such as Paris, Regensburg and Naples.[35][36] Catholic religious orders of the Augustinians' and Benedictines' rules contained ritual purification,[37] and inspired by Benedict of Nursia encouragement for the practice of therapeutic bathing; Benedictine monks played a role in the development and promotion of spas.[34] Protestantism also played a prominent role in the development of the British spas.[34]

Roman style public baths were introduced on a limited scale by returning crusaders in the 11th and 12th centuries,[38] who had enjoyed warm baths in the Middle East. These, however, rapidly degenerated into brothels or at least the reputation as such and were closed down at various times. For instance, in England during the reign of Henry II, bath houses, called bagnios from the Italian word for bath, were set up in Southwark on the river Thames. They were all officially closed down by Henry VIII in 1546 due to their negative reputation.

Modern public bathing

[edit]A notable exception to this trend was in Finland and Scandinavia, where the sauna remained a popular phenomenon, even expanding during the Reformation period, when European bath houses were being destroyed. Finnish saunas remain an integral and ancient part of the way of life there. They are found on the lake shore, in private apartments, corporate headquarters, at the Parliament House and even at the depth of 1,400 metres (4,600 ft) in Pyhäsalmi Mine. The sauna is an important part of the national identity[39] and those who have the opportunity usually take a sauna at least once a week.[40]

British Empire

[edit]

The first modern public baths were opened in Liverpool in 1829. The first known warm fresh-water public wash house was opened in May 1842.[41][42]

The popularity of wash-houses was spurred by the newspaper interest in Kitty Wilkinson, an Irish immigrant "wife of a labourer" who became known as the Saint of the Slums.[43] In 1832, during a cholera epidemic, Wilkinson took the initiative to offer the use of her house and yard to neighbours to wash their clothes, at a charge of a penny per week,[41] and showed them how to use a chloride of lime (bleach) to get them clean. She was supported by the District Provident Society and William Rathbone. In 1842 Wilkinson was appointed baths superintendent.[44][45]

In Birmingham, around ten private baths were available in the 1830s. Whilst the dimensions of the baths were small, they provided a range of services.[46] A major proprietor of bath houses in Birmingham was a Mr. Monro who had had premises in Lady Well and Snow Hill.[47] Private baths were advertised as having healing qualities and being able to cure people of diabetes, gout and all skin diseases, amongst others.[47] On 19 November 1844, it was decided that the working class members of society should have the opportunity to access baths, in an attempt to address the health problems of the public. On 22 April and 23 April 1845, two lectures were delivered in the town hall urging the provision of public baths in Birmingham and other towns and cities.

After a period of campaigning by many committees, the Public Baths and Wash-houses Act received royal assent on 26 August 1846. The Act empowered local authorities across the country to incur expenditure in constructing public swimming baths out of its own funds.[48]

The first London public baths was opened at Goulston Square, Whitechapel, in 1847 with the Prince Consort laying the foundation stone.[49][50]

The introduction of bath houses into British culture was a response to the public's desire for increased sanitary conditions, and by 1915 most towns in Britain had at least one.[51]

Hot baths

[edit]

Victorian Turkish baths (based on the traditional Muslim bathhouses which are derived from the Roman bath) were introduced to Britain by David Urquhart, diplomat and sometime Member of Parliament for Stafford, who for political and personal reasons wished to popularize Turkish culture. In 1850 he wrote The Pillars of Hercules, a book about his travels in 1848 through Spain and Morocco. He described the system of dry hot-air baths (little-changed since Roman times) which were used there and in the Ottoman Empire. In 1856 Richard Barter read Urquhart's book and worked with him to construct such a bath. After a number of unsuccessful attempts, Barter opened the first bath of this type at St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment near Blarney, County Cork, Ireland.[52]

The following year, the first public bath of its type to be built in mainland Britain since Roman times was opened in Manchester, and the idea spread rapidly. It reached London in July 1860, when Roger Evans, a member of one of Urquhart's Foreign Affairs Committees, opened a Turkish bath at 5 Bell Street, near Marble Arch. During the following 150 years, over 700 Turkish baths opened in Britain, including those built by municipal authorities as part of swimming pool complexes.

Similar baths opened in other parts of the British Empire. Dr. John Le Gay Brereton opened a Turkish bath in Sydney, Australia in 1859, Canada had one by 1869, and the first in New Zealand was opened in 1874. Urquhart's influence was also felt outside the Empire when in 1861, Dr Charles H Shepard opened the first Turkish baths in the United States at 63 Columbia Street, Brooklyn Heights, New York, most probably on 3 October 1863.[53]

Russia

[edit]

Washing and thermal body treatments with steam and accessories such as a bunch of birch branches have been traditionally carried out in banyas. This tradition was born in rural areas, Russia being a spacious country with a farming population dominating until World War II. Farmers did not have inside their log cabins running water supply and hot bathtubs for washing their bodies, so they either used for their washing heat and space inside their Russian stoves or built from logs, like the cottage itself, a one-family banya bath outhouse behind their dwelling on the family's land plot. It was usually a smallish wooden cabin with a low entrance and no more than one small window to keep heat inside. Traditionally, the family washed their bodies completely once a week before the day of the Bible-prescribed rest (Sunday) as having a (steam) bath meant having to get and bring in a considerable amount of firewood and water and spending time off other farm work heating the bathhouse.

With the growth of Russian big cities since the 18th century, public baths were opened in them and then back in villages. While the richer urban circles could afford to have an individual bathroom with a bathtub in their apartments (since the late 19th century with running water), the lower classes necessarily used public steambaths – special big buildings which were equipped with developed side catering services enjoyed by the merchants with a farming background.

Since the first half of the 20th century running unheated drinking water supply has been made available virtually to all inhabitants of multi-story apartment buildings in cities, but if such dwellings were built during the 1930s and not updated later, they do not have hot running water (except for central heating) or space to accommodate a bathtub, plumbing facilities being limited in them only to a kitchen sink and a small toilet room with a toilet seat. Thus the dwellers of such apartments, on a par with those living in the part of pre-1917-built blocks of flats which had not undergone cardinal renovation, would have no choice but to use public bathhouses.

Since the 1950s in cities, towns, and many rural areas more comfortable dwelling became a nationally required standard, and almost all apartments are designed with both cold and hot water supply, and a bathroom with a bathtub, but a percentage of people living in them still go to public steam baths for health treatments with steam, tree branches, aromatic oils.

United States

[edit]The building of public baths in the United States began in the 1890s. Public baths were created to improve the health and sanitary condition of the working classes, before personal baths became commonplace.

One pioneering public bathhouse was the well-appointed James Lick Baths building, with laundry facilities, given to the citizens of San Francisco in 1890 by the James Lick estate for their free use.[54] The Lick bathhouse continued as a public amenity until 1919. Other early examples such as the 1890 West Side Natatorium in Milwaukee, the first of Chicago's in 1894, and the 1891 People's Baths on the Lower East Side of Manhattan were alike in their explicit spirit of social improvement—the People's Baths were organized by Simon Baruch and financed by the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor.[55]

In an 1897 comparison to Pittsburgh, which had no municipal baths, Philadelphia was equipped with a dozen, "distributed through the very poorest quarters of the city," each with a concrete pool and 80 dressing rooms. Every pool was drained, flushed and swept twice a week, prior to the two days set aside for ladies only, Mondays and Thursdays.[56] The average number of visitors to the Philadelphia baths every week was about 28,000, with a "great crush" of boys appearing after school hours, boys who were likely to ignore their 30-minute time limits. Operators discouraged the use of soap.[56] By 1904 Pittsburgh would have its third municipal bath, the Wash House and Public Building, built by private contributors but maintained by the city.[57]

A New York state law of 1895 required every city over 50,000 in population maintain as many public baths as their Boards of Health deemed necessary, providing hot and cold water for at least 14 hours a day.[58] Despite that mandate, the first civic bathhouse in New York City, the Rivington Street municipal bath on the Lower East Side, opened five years later.

This amounted to a national bath-building movement that peaked in the decade between 1900 and 1910.[55] By 1904, eight of the nation's ten most populous cities had year-round bathhouses available to the working class. In 1922, 40 cities across the country maintained at least one or two public facilities, and the city with the largest system of baths was New York City, with 25.[55]

Other notable constructions of the period/include Bathhouse Row[59] in the spa resort town of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and the Asser Levy Public Baths in New York City, completed in 1908.

Gallery

[edit]-

Alfred Laliberté's Les petits Baigneurs, 1915 restored 1992 at Maisonneuve public baths, Montreal, Quebec

-

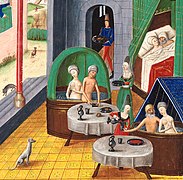

Bathing in 1450

-

Bathing in 1568

-

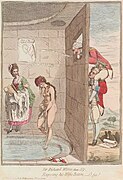

A woman bathing is spied upon through a window, England, 1782

-

Ancient Ruins Used as Public Baths by Hubert Robert (1798)

-

Bagno del Papa in Viterbo

-

Agkistro Byzantine bath

See also

[edit]- Bathing culture in Yangzhou – China

- Gymnasium – ancient Greece

- Steam shower

- Sweat lodge – Native American

- Gay bathhouse

- Water park

References

[edit]- ^ a b Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ^ "An Insight into an Egyptian Intangible Cultural Heritage Tradition: The Hammām". International Journal of Heritage and Museum Studies. 2 (1). Egypts Presidential Specialized Council for Education and Scientific Research: 51–67. 2020-10-01. doi:10.21608/ijhms.2020.188742. ISSN 2735-3850. S2CID 237439213.

- ^ Redon, Bérangère (2017). Collective baths in Egypt 2 : new discoveries and perspectives : Balaneîa = Thermae = Hammâmât. Le Caire. ISBN 978-2-7247-0696-3. OCLC 1002185387.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Sun, Jiahui (1 July 2021). "Bathing in Ancient Times". theworldofchinese.

- ^ a b c d "Ancient Chinese Bath Culture". viewofchina. 30 April 2019.

- ^ Golas, Peter J and Needham, Joseph (1999) Science and Civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–91. ISBN 0-521-58000-5

- ^ "Marco Polo's Descriptions of China". Facts and Details. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Marco Polo's World". Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "How to visit a Korean bathhouse for the first time".

- ^ Water Conduits in the Kathmandu Valley (2 vols.) by Raimund O.A. Becker-Ritterspach, ISBN 9788121506908, Published by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India, 1995

- ^ Kathmandu water spouts, lost and found cases Archived 2019-12-06 at the Wayback Machine by Purushottam P. Khatri, The Rising Nepal, 1 June 2019, retrieved 6 December 2019

- ^ a b Clark, Scott (1994). Clark – 1994. ISBN 978-0-8248-1657-5.

backcover Misogi

- ^ Clark, Scott (1994). Clark – 1994. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8248-1657-5.

Gyōzui

- ^ "The Majestic Beauty of the Ratu Boko Palace ruins". Wonderful Indonesia. Archived from the original on 2014-06-25. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ^ Sita W. Dewi (9 April 2013). "Tracing the glory of Majapahit". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Pura Tirta Empul". Burari Bali. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Daily life in ancient Rome : a sourcebook. Brian K. Harvey. Indianapolis. 2016. ISBN 978-1-58510-795-7. OCLC 924682988.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Professor Garrett G. Fagan – Audio & Video Lectures". The Great Courses. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ Fagan, Garrett G. (2002). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. ISBN 0-472-08865-3.

- ^ a b c d M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Bath". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Sibley, Magda. "The Historic Hammams of Damascus and Fez: Lessons of Sustainability and Future Developments". The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture.

- ^ a b Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ a b c Sourdel-Thomine, J.; Louis, A. (2012). "Ḥammām". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- ^ "About Bath Houses, Turkish Baths and Sauna Culture and Bath Resources". Aquariussauna.com. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 2. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. p. 359 [180a] (Hil. Ta'aniyot 5:6). OCLC 122758200.; cf. Joseph Karo, Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 554:1)

- ^ a b c d e f Babylonian Talmud (vol. 16: Avodah Zarah, Eduyoth, Horayoth), appendix, Tractate Kallah Rabbati (chapter 10), p. 55a in the Or Hachaim Institutions edition (in Hebrew)

- ^ Jastrow, M., ed. (2006), Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, p. 1517, OCLC 614562238, s.v. שבר I (end)

- ^ Eisenstein, Judah D. (1970). A Digest of Jewish Laws and Customs - in Alphabetical Order (Ozar Dinim u-Minhagim) (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv: Ḥ. mo. l. pp. 250–251 (s.v. מרחץ). OCLC 54817857. (reprinted from 1922 and 1938 editions of the Hebrew Publishing Co., New York)

- ^ Warsh, Cheryl Krasnick (2006). Children's Health Issues in Historical Perspective. Veronica Strong-Boag. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-88920-912-1.

... Thus bathing also was considered a part of good health practice. For example, Tertullian attended the baths and believed them hygienic. Clement of Alexandria, while condemning excesses, had given guidelines for Christian] who wished to attend the baths ...

- ^ Thurlkill, Mary (2016). Sacred Scents in Early Christianity and Islam: Studies in Body and Religion. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0-7391-7453-1.

... Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215 CE) allowed that bathing contributed to good health and hygiene ... Christian skeptics could not easily dissuade the baths' practical popularity, however; popes continued to build baths situated within church basilicas and monasteries throughout the early medieval period ...

- ^ a b Squatriti, Paolo (2002). Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400-1000, Parti 400–1000. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-52206-9.

... but baths were normally considered therapeutic until the days of Gregory the Great, who understood virtuous bathing to be bathing "on account of the needs of body" ...

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- ^ Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou, Eutychia; Tourta, A. (1997). Wandering in Byzantine Thessaloniki.

- ^ a b c Bradley, Ian (2012). Water: A Spiritual History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-6767-5.

- ^ Black, Winston (2019). The Middle Ages: Facts and Fictions. ABC-CLIO. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4408-6232-8.

Public baths were common in the larger towns and cities of Europe by the twelfth century.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Harald (2005). Perception and Action in Medieval Europe. Boydell & Brewer. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84383-146-4.

The evidence of early medieval laws that enforced punishments for the destruction of bathing houses suggests that such buildings were not rare. That they ... took a bath every week. At places in southern Europe, Roman baths remained in use or were even restored ... The Paris city scribe Nicolas Boileau noted the existence of twenty-six public baths in Paris in 1272

- ^ Hembry, Phyllis (1990). The English Spa, 1560–1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3391-5.

- ^ Wheatcroft (2003) p. 73.

- ^ Valtakari, P. "Finnish Sauna Culture – Not Just a Cliché". The Finnish Sauna Society.

- ^ Korhonen, N. (April 1998). "The sauna – a sacred place". Universitas Helsingiensis. Helsinki: Helsinki University.

- ^ a b Ashpitel, Arthur (1851), Observations on baths and wash-houses, pp. 2–14, JSTOR 60239734, OCLC 501833155

- ^ Metcalfe, Richard (1877), Sanitas Sanitatum et Omnia Sanitas, vol. 1, Co-operative printing company, p. 3

- ^ "'Slum Saint' honored with statue". BBC News. 4 February 2010.

- ^ Wohl, Anthony S. (1984), Endangered lives: public health in Victorian Britain, Taylor & Francis, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-416-37950-1

- ^ Rathbone, Herbert R. (1927), Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson of Liverpool, 1786–1860: with a short account of Thomas Wilkinson, her husband, H. Young & Sons

- ^ West, William (1830). Topography of Warwickshire.

- ^ a b "Private Bath Advertisements". The Birmingham Journal. 1851-05-17.

- ^ "Baths and Wash-Houses". The Times. 1846-07-22. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011.

Yesterday the bill, as amended by the committee, for promoting the voluntary establishment in boroughs and parishes in England and Wales of public baths and wash-houses was printed.

- ^ "Classified Advertising". The Times. 1847-07-26. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011.

Model Public Baths, Goulston-square, Whitechapel. The BATHS for men and boys are now OPEN from 5 in the morning till 10 at night. Charges – first-class (two towels), cold bath 5d., warm bath 6d.; second-class (one towel), cold bath 1d, warm bath 2d. Every bath is in a private room.

- ^ Metcalfe, Richard (1877), Sanitas Sanitatum et Omnia Sanitas, vol. 1, Co-operative printing company, p. 7

- ^ Sally Sheard* (2014-05-02). "Profit is a Dirty Word: The Development of Public Baths and Wash-houses in Britain 1847–1915 – SHEARD 13 (1): 63 – Social History of Medicine". Shm.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on 2006-10-03. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ^ Shifrin, Malcolm (3 October 2008), "St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment, Blarney, Co. Cork", Victorian Turkish Baths: Their origin, development, and gradual decline, archived from the original on 11 May 2011, retrieved 12 December 2009

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 3 October 1863

- ^ "James Lick's Public Baths – A Building the City May Well Feel Proud Of". San Francisco Call. 2 November 1890. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Williams, Marilyn Thornton (1 January 1991). Washing "The Great Unwashed": Public Baths in Urban America, 1840–1920. The Ohio State University Press. pp. 39, 44. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b Bayard, "Meg," Mary Temple (14 March 1897). "The Great Unwashed". Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Former Pittsburgh Wash House & Public Baths Nominated for Historic Landmark Status". Preservation Pittsburgh. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Veiller, Lawrence (1 January 1903). The Tenement House Problem Including the Report of the New York State Tenement House Commission of 1900 · Volume 2. Macmillan. p. 42. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "FORDYCE Bathhouse General History". asms.k12.ar.us. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

Bibliography

[edit]- Clark, Scott (1994). Japan, a view from the bath. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1657-9.