Strike action

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labor |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the Industrial Revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines. As striking became a more common practice, governments were often pushed to act (either by private business or by union workers). When government intervention occurred, it was rarely neutral or amicable. Early strikes were often deemed unlawful conspiracies or anti-competitive cartel action and many were subject to massive legal repression by state police, federal military power, and federal courts.[1] Many Western nations legalized striking under certain conditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Strikes are sometimes used to pressure governments to change policies. Occasionally, strikes destabilize the rule of a particular political party or ruler; in such cases, strikes are often part of a broader social movement taking the form of a campaign of civil resistance. Notable examples are the 1980 Gdańsk Shipyard and the 1981 Warning Strike led by Lech Wałęsa. These strikes were significant in the long campaign of civil resistance for political change in Poland, and were an important mobilizing effort that contributed to the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of communist party rule in Eastern Europe.[2] Another example is the general strike in Weimar Germany that followed the March 1920 Kapp Putsch. It was called by the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and received such broad support that it resulted in the collapse of the putsch.[3]

History

[edit]

Origin of the term

[edit]The use of the English word "strike" to describe a work protest was first seen in 1768, when sailors, in support of demonstrations in London, "struck" or removed the topgallant sails of merchant ships at port, thus crippling the ships.[4][5][6]

Pre-industrial strikes

[edit]

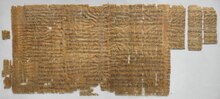

The first historically certain account of strike action was in ancient Egypt on 14 November in 1152 BCE, when artisans of the Royal Necropolis at Deir el-Medina walked off their jobs in protest at the failure of the government of Ramesses III to pay their wages on time and in full.[7][8] The royal government ended the strike by raising the artisans' wages.

The first Jewish source for the idea of a labor strike appears in the Talmud, which records that the bakers who prepared showbread for the altar went on strike.[9]

An early predecessor of the general strike may have been the secessio plebis in ancient Rome. In The Outline of History, H. G. Wells characterized this event as "the general strike of the plebeians; the plebeians seem to have invented the strike, which now makes its first appearance in history."[10] Their first strike occurred because they "saw with indignation their friends, who had often served the state bravely in the legions, thrown into chains and reduced to slavery at the demand of patrician creditors".[10]

During and after the Industrial Revolution

[edit]

The strike action only became a feature of the political landscape with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. For the first time in history, large numbers of people were members of the industrial working class; they lived in towns and cities, exchanging their labor for payment. By the 1830s, when the Chartist movement was at its peak in Britain, a true and widespread 'workers consciousness' was awakening. In 1838, a Statistical Society of London committee "used the first written questionnaire… The committee prepared and printed a list of questions 'designed to elicit the complete and impartial history of strikes.'"[11]

In 1842 the demands for fairer wages and conditions across many different industries finally exploded into the first modern general strike. After the second Chartist Petition was presented to Parliament in April 1842 and rejected, the strike began in the coal mines of Staffordshire, England, and soon spread through Britain affecting factories, cotton mills in Lancashire and coal mines from Dundee to South Wales and Cornwall.[12] Instead of being a spontaneous uprising of the mutinous masses, the strike was politically motivated and was driven by an agenda to win concessions. As much as half of the then industrial work force were on strike at its peak – over 500,000 men.[13] The local leadership marshaled a growing working class tradition to politically organize their followers to mount an articulate challenge to the capitalist, political establishment. Friedrich Engels, an observer in London at the time, wrote:

by its numbers, this class has become the most powerful in England, and woe betide the wealthy Englishmen when it becomes conscious of this fact … The English proletarian is only just becoming aware of his power, and the fruits of this awareness were the disturbances of last summer.[14]

As the 19th century progressed, strikes became a fixture of industrial relations across the industrialized world, as workers organized themselves to collectively bargain for better wages and standards with their employers. Karl Marx condemned the theory of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon criminalizing strike action in his work The Poverty of Philosophy.[15]

Recognition strikes

[edit]A recognition strike is an industrial strike implemented in order to force a particular employer or industry to recognize a trade union as the legitimate collective bargaining agent for a company's workers.[16][17][18] In 1949, their use in the United States was described as "a weapon used with varying results by labor for the last forty years or more". One example cited was the successful formation of the United Auto Workers, which achieved recognition from General Motors through the Flint sit-down strike of 1936-37.[19] They were more common prior to the advent of modern American labor law (including the National Labor Relations Act), which introduced processes legally compelling an employer to recognize the legitimacy of properly certified unions.[19][16]

Two examples include the U.S. Steel recognition strike of 1901, and the subsequent coal strike of 1902.[20] A 1936 study of strikes in the United States indicated that about one third of the total number of strikes between 1927 and 1928, and over 40 percent in 1929, were due to "demands for union recognition, closed shop, and protest against union discrimination and violation of union agreements".[21] A 1988 study of strike activity and unionization in non-union municipal police departments between 1972 and 1978 found that recognition strikes were carried out "primarily where bargaining laws [provided] little or no protection of bargaining rights."[22]

In 1937, there were 4,740 strikes in the United States.[23] This was the greatest strike wave in American labor history. The number of major strikes and lockouts in the U.S. fell by 97% from 381 in 1970 to 187 in 1980 to only 11 in 2010. Companies countered the threat of a strike by threatening to close or move a plant.[24][25]

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted in 1967, ensures the right to strike in Article 8. The European Social Charter, adopted in 1961, also ensures the right to strike in Article 6.

The Farah Strike, 1972–1974, labeled the "strike of the century," was organized and led by Mexican American women predominantly in El Paso, Texas.[26]

Frequency and duration

[edit]

Strikes are rare, in part because many workers are not covered by a collective bargaining agreement.[27] Strikes that do occur are generally fairly short in duration.[27] Labor economist John Kennan notes:

In Britain in 1926 (the year of the general strike) about 9 workdays per worker were lost due to strikes. In 1979, the loss due to strikes was a little more than one day per worker. These are the extreme cases. In the 79 years following 1926, the number of workdays lost in Britain was less than 2 hours per year per worker. In the U.S., idleness due to strikes never exceeded one half of one percent of total working days in any year during the period 1948-2005; the average loss was 0.1% per year. Similarly, in Canada over the period 1980-2005, the annual number of work days lost due to strikes never exceeded one day per worker; on average over this period lost worktime due to strikes was about one-third of a day per worker. Although the data are not readily available for a broad sample of developed countries, the pattern described above seems quite general: days lost due to strikes amount to only a fraction of a day per worker per annum, on average, exceeding one day only in a few exceptional years.[27]

Since the 1990s, strike actions have generally further declined, a phenomenon that might be attributable to lower information costs (and thus more readily available access to information on economic rents) made possible by computerization and rising personal indebtedness, which increases the cost of job loss for striking workers.[27][28][29] In the United States, the number of workers involved in major work stoppages (including strikes and, less commonly, lockouts) that involved at least a thousand workers for at least one full shift generally declined from 1973 to 2017 (coinciding with a general decrease in overall union membership), before substantially increasing in 2018 and 2019.[30] In the 2018 and 2019 period, 3.1% of union members were involved in a work stoppage each year on average, these strikes also contained more workers than ever recorded with an average of 20,000 workers participating in each major work stoppage in 2018 and 2019.[30]

By country

[edit]For the period from 1996 to 2000, the ten countries with the most strike action (measured by average number of days not worked for every 1000 employees) were as follows:[31]

| Country | Days not worked |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 296 |

| Iceland | 244 |

| Canada | 217 |

| Spain | 189 |

| Norway | 135 |

| South Korea | 95 |

| Ireland | 90 |

| Australia | 86 |

| Italy | 76 |

| France | 67 |

Variations

[edit]

Most strikes are organized by labor unions during collective bargaining as a last resort. The object of collective bargaining is for the employer and the union to come to an agreement over wages, benefits, and working conditions. A collective bargaining agreement may include a clause (a contractual "no-strike clause") which prohibits the union from striking during the term of the agreement.[32] Under U.S. labor law, a strike in violation of a no-strike clause is not a protected concerted activity.[32]

The scope of a no-strike clause varies; generally, the U.S. courts and National Labor Relations Board have determined that a collective bargaining agreement's no-strike clause has the same scope as the agreement's arbitration clauses, such that "the union cannot strike over an arbitrable issue."[32] The U.S. Supreme Court held in Jacksonville Bulk Terminals Inc. v. International Longshoremen's Association (1982), a case involving the International Longshoremen's Association refusing to work with goods for export to the Soviet Union in protest against its invasion of Afghanistan, that a no-strike clause does not bar unions from refusing to work as a political protest (since that is not an "arbitrable" issue), although such activity may lead to damages for a secondary boycott.[32] Whether a no-strike clause applies to sympathy strikes depends on the context.[32] Some in the labor movement consider no-strike clauses to be an unnecessary detriment to unions in the collective bargaining process.[33]

Occasionally, workers decide to strike without the sanction of a labor union, either because the union refuses to endorse such a tactic, or because the workers involved are non-unionized. Strikes without formal union authorization are also known as wildcat strikes.

In many countries, wildcat strikes do not enjoy the same legal protections as recognized union strikes, and may result in penalties for the union members who participate, or for their union. The same often applies in the case of strikes conducted without an official ballot of the union membership, as is required in some countries such as the United Kingdom.

A strike may consist of workers refusing to attend work or picketing outside the workplace to prevent or dissuade people from working in their place or conducting business with their employer. Less frequently, workers may occupy the workplace, but refuse to work. This is known as a sit-down strike. A similar tactic is the work-in, where employees occupy the workplace but still continue work, often without pay, which attempts to show they are still useful, or that worker self-management can be successful. For instance, this occurred with factory occupations in the Biennio Rosso strikes – the "two red years" of Italy from 1919 to 1920.[citation needed]

Another unconventional tactic is work-to-rule (also known as an Italian strike, in Italian: Sciopero bianco), in which workers perform their tasks exactly as they are required to but no better. For example, workers might follow all safety regulations in such a way that it impedes their productivity or they might refuse to work overtime. Such strikes may in some cases be a form of "partial strike" or "slowdown".

During the development boom of the 1970s in Australia, the Green ban was developed by certain unions described by some as more socially conscious. This is a form of strike action taken by a trade union or other organized labor group for environmentalist or conservationist purposes. This developed from the black ban, strike action taken against a particular job or employer in order to protect the economic interests of the strikers.

United States labor law also draws a distinction, in the case of private sector employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act, between "economic" and "unfair labor practice" strikes. An employer may not fire, but may permanently replace, workers who engage in a strike over economic issues. On the other hand, employers who commit unfair labor practices (ULPs) may not replace employees who strike over them, and must fire any strikebreakers they have hired as replacements in order to reinstate the striking workers.

Strikes may be specific to a particular workplace, employer, or unit within a workplace, or they may encompass an entire industry, or every worker within a city or country. Strikes that involve all workers, or a number of large and important groups of workers, in a particular community or region are known as general strikes. Under some circumstances, strikes may take place in order to put pressure on the State or other authorities or may be a response to unsafe conditions in the workplace.

A sympathy strike is a strike action in which one group of workers refuses to cross a picket line established by another as a means of supporting the striking workers. Sympathy strikes, once the norm in the construction industry in the United States, have been made much more difficult to conduct, due to decisions of the National Labor Relations Board permitting employers to establish separate or "reserved" gates for particular trades, making it an unlawful secondary boycott for a union to establish a picket line at any gate other than the one reserved for the employer it is picketing. Still, the practice continues to occur; for example, some Teamsters contracts often protect members from disciplinary action if a member refuses to cross a picket line.[34] Sympathy strikes may be undertaken by a union as an organization, or by individual union members choosing not to cross a picket line.

A jurisdictional strike in United States labor law refers to a concerted refusal to work undertaken by a union to assert its members' right to particular job assignments and to protest the assignment of disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers.

A rolling strike refers to a strike where only some employees in key departments or locations go on strike. These strikes are performed in order to increase stakes as negotiations draw on and to be unpredictable to the employer. Rolling strikes also serve to conserve strike funds.

A student strike involves students (sometimes supported by faculty) refusing to attend classes. In some cases, the strike is intended to draw media attention to the institution so that the grievances that are causing the students to strike can be aired before the public; this usually damages the institution's (or government's) public image. In other cases, especially in government-supported institutions, the student strike can cause a budgetary imbalance and have actual economic repercussions for the institution.

A hunger strike is a deliberate refusal to eat. Hunger strikes are often used in prisons as a form of political protest. Like student strikes, a hunger strike aims to worsen the public image of the target.

A "sickout", or (especially by uniformed police officers) "blue flu", is a type of strike action in which the strikers call in sick. This is used in cases where laws prohibit certain employees from declaring a strike. Police, firefighters, air traffic controllers, and teachers in some U.S. states are among the groups commonly barred from striking usually by state and federal laws meant to ensure the safety or security of the general public.

Newspaper writers may withhold their names from their stories as a way to protest actions of their employer.[35]

Activists may form "flying squad" groups for strikes or other actions, a form of picketing, to disrupt the workplace or another aspect of capitalist production: supporting other strikers or unemployed workers, participating in protests against globalization, or opposing abusive landlords.[36]

Legal prohibitions

[edit]Canada

[edit]On 30 January 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that there is a constitutional right to strike.[37] In this 5–2 majority decision, Justice Rosalie Abella ruled that "[a]long with their right to associate, speak through a bargaining representative of their choice, and bargain collectively with their employer through that representative, the right of employees to strike is vital to protecting the meaningful process of collective bargaining…" [paragraph 24]. This decision adopted the dissent by Chief Justice Brian Dickson in a 1987 Supreme Court ruling on a reference case brought by the province of Alberta (Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta)). The exact scope of this right to strike remains unclear.[38]

Prior to this Supreme Court decision, the federal and provincial governments had the ability to introduce "back-to-work legislation", a special law that blocks the strike action (or a lockout) from happening or continuing. Canadian governments could also have imposed binding arbitration or a new contract on the disputing parties. Back-to-work legislation was first used in 1950 during a railway strike, and as of 2012 had been used 33 times by the federal government for those parts of the economy that are regulated federally (grain handling, rail and air travel, and the postal service), and in more cases provincially. In addition, certain parts of the economy can be proclaimed "essential services" in which case all strikes are illegal.[39]

Examples include when the government of Canada passed back-to-work legislation during the 2011 Canada Post lockout and the 2012 CP Rail strike, thus effectively ending the strikes. In 2016, the government's use of back-to-work legislation during the 2011 Canada Post lockout was ruled unconstitutional, with the judge specifically referencing the Supreme Court of Canada's 2015 decision in Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v Saskatchewan.[40]

People's Republic of China and the former Soviet Union

[edit]

In some Marxist–Leninist states, such as the People's Republic of China, striking was illegal and viewed as counter-revolutionary, and labor strikes are considered to be taboo in most East Asian cultures. In 1976, China signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which guaranteed the right to unions and striking, but Chinese officials declared that they had no interest in allowing these liberties.[41] In June 2008, the municipal government in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone introduced draft labor regulations, which a labor rights advocacy group says would, if implemented and enforced, virtually restore Chinese workers' right to strike.[42] [obsolete source]

In the Soviet Union, strikes occurred throughout the existence of the USSR, most notably in the 1930s. After World War II, they diminished both in number and in scale.[43] Trade unions in the Soviet Union served in part as a means to educate workers about the country's economic system. Vladimir Lenin referred to trade unions as "Schools of Communism".[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

France

[edit]

In France, the first law aimed at limiting the ability of workers to take collective action was the Le Chapelier Law, passed by the National Assembly on 14 June 1791 and which introduced the "crime of coalition." In his speech in support of the law, the titular author Isaac René Guy le Chapelier explained that it "must be without a doubt permitted for all citizens to assemble," but he maintained that it "must not be permitted for citizens from certain professions to assemble for their so-called common interests."[44]

Strike actions were specifically banned with the passage of Napoleon's French Penal Code of 1810. Article 415 of the Code declared that participants in an attempted strike action would be subject to an imprisonment of between one and three months and that the organizers of the attempted strike action would be subject to an imprisonment of between two and five years.[45]

The right to strike under the current French Fifth Republic has been recognized and guaranteed by the Preamble to the French Constitution of 27 October 1946 ever since the Constitutional Council's 1971 decision on the freedom of association recognized that document as being invested with constitutional value.

A "minimum service" during strikes in public transport was a promise of Nicolas Sarkozy during his campaign for the French presidential election. A law "on social dialogue and continuity of public service in regular terrestrial transports of passengers" was adopted on 12 August 2007, and it took effect on 1 January 2008.

Italy

[edit]In Italy, the right to strike is guaranteed by the Constitution (article 40). The law number 146 of 1990 and law number 83 of 2000[46] regulate the strike actions. In particular, they impose limitations for the strikes of workers in public essential services, i.e., the ones that "guarantee the personality rights of life, health, freedom and security, movements, assistance and welfare, education, and communications". These limitations provide a minimum guarantee for these services and punish violations. Similar limitations are applied to workers in the private sector whose strike can affect public services. The employer is explicitly forbidden to apply sanctions to employees participating to the strikes, with the exception of the aforementioned essential services cases.

The government, under exceptional circumstances, can impose the precettazione of the strike, i.e., can force the postponement, cancellation or duration reduction of a national-wide strike. The prime minister has to justify the decision of applying the precettazione in front of the parliament. For local strikes, precettazione can also be applied by a decision of the prefect. The employees refusing to work after the precettazione takes effect may be subject of a sanction or even a penal action (for a maximum of 4 years of prison) if the illegal strike causes the suspension of an essential service.

Precettazione has been rarely applied, usually after several days of strikes affecting transport or fuel services or extraordinary events. Recent cases include the cancellation of the 2015 strike of the company providing transportation services in Milan during Expo 2015, and the 2007 precettazione to stop the strike of the truck drivers that was causing food and fuel shortage after several days of strike.

United Kingdom

[edit]Legislation was enacted in the aftermath of the 1919 police strikes, forbidding British police from both taking industrial action, and discussing the possibility with colleagues.[47]

In January 1951 during the Labour Attlee ministry, Attorney-General Hartley Shawcross left his name to a Parliamentary principle in a defense of his conduct regarding an illegal strike: that the Attorney-General "is not to be put, and is not put, under pressure by his colleagues in the matter" of whether or not to establish criminal proceedings.[48][49]

The Industrial Relations Act 1971 was repealed through the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act 1974, sections of which were repealed by the Employment Act 1982.

The Code of Practice on Industrial Action Ballots and Notices, and sections 22 and 25 of the Employment Relations Act 2004, which concern industrial action notices, commenced on 1 October 2005.

The Police Federation, which was created at the time to deal with employment grievances and to provide representation to police officers, attempted to put pressure on the Blair ministry and at the time repeatedly threatened strike action.[47]

Prison officers have gained and lost the right to strike over the years; in the 2010s, despite it being illegal, they walked out on 15 November 2016,[50] and again on 14 September 2018.[51]

Germany

[edit]In Germany, the Basic Law bans civil servants from going on strike, and the Federal Constitutional Court confirmed that teachers were not permitted to strike.[52] As of December 2023, the matter whether the decision violated teachers' human rights under the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) is pending at the European Court of Human Rights.[52]

United States

[edit]

The Railway Labor Act bans strikes by United States airline and railroad employees except in narrowly defined circumstances. The National Labor Relations Act generally permits strikes, but provides a mechanism to enjoin from striking workers in industries in which a strike would create a national emergency. As of 2021[update], the federal government most recently invoked these statutory provisions to obtain an injunction requiring the International Longshore and Warehouse Union to return to work in 2002 after having been locked out by the employer group, the Pacific Maritime Association.

Some jurisdictions prohibit all strikes by public employees, under laws such as the "Taylor Law" in New York. Other jurisdictions impose strike bans only on certain categories of workers, particularly those regarded as critical to society: police, teachers and firefighters are among the groups commonly barred from striking in these jurisdictions. Some states, such as New Jersey, Michigan, Iowa or Florida, do not allow teachers in public schools to strike. Workers have sometimes circumvented these restrictions by falsely claiming inability to work due to illness – this is sometimes called a "sickout" or "blue flu", the latter receiving its name from the uniforms worn by police officers, who are traditionally prohibited from striking. The term "red flu" has sometimes been used to describe this action when undertaken by firefighters.

Under federal law, federal employees who participate in a strike, or who assert the right to strike against the US government, are barred from retaining their employment.[53]

Often, specific regulations on strike actions exist for employees in prisons. The Code of Federal Regulations declares "encouraging others to refuse to work, or to participate in a work stoppage" by prisoners to be a "High Severity Level Prohibited Act" and authorizes solitary confinement for periods of up to a year for each violation.[54] The California Code of Regulations states that "[p]articipation in a strike or work stoppage", "[r]efusal to perform work or participate in a program as ordered or assigned", and "[r]ecurring failure to meet work or program expectations within the inmate's abilities when lesser disciplinary methods failed to correct the misconduct" by prisoners is "serious misconduct" under §3315(a)(3)(L), leading to gang affiliation under CCR §3000.[55]

Postal workers involved in 1978 wildcat strikes in Jersey City, Kearny, New Jersey, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. were fired under the presidency of Jimmy Carter, and President Ronald Reagan fired air traffic controllers and the PATCO union after the air traffic controllers' strike of 1981.

The West Virginia teacher's strike in 2018 inspired teachers in other states, including Oklahoma, Colorado, and Arizona, to take similar action.[56]

Jurisprudence and philosophy

[edit]Strike actions have also been discussed from the perspective of jurisprudence and philosophy, with issues being raised such as whether people have a right to strike, the interaction of strikes with other rights, civil order, coercion, justice and the interplay between striking and contracts.[57][58][59][60][61]

Strikebreakers

[edit]

A strikebreaker (sometimes derogatorily called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who are not employed by the company prior to the trade union dispute, but rather hired after or during the strike to keep the organization running. "Strikebreakers" may also refer to workers (union members or not) who cross picket lines to work.

Irwin, Jones, McGovern (2008)[full citation needed] believe that the term "scab" is part of a larger metaphor involving strikes. They argue that the picket line is symbolic of a wound and those who break its borders to return to work are the scabs who bond that wound. Others have argued that the word is not a part of a larger metaphor but, rather, was an old-fashioned English insult whose meaning narrowed over time.

"Blackleg" is an older word and is found in the 19th-century folk song "Blackleg Miner" which originated in Northumberland. The term does not necessarily owe its origins to this tune of unknown origin.

Union strikebreaking

[edit]The concept of union strikebreaking or union scabbing refers to any circumstance in which union workers themselves cross picket lines to work.

Unionized workers are sometimes required to cross the picket lines established by other unions due to their organizations having signed contracts which include no-strike clauses. The no-strike clause typically requires that members of the union not conduct any strike action for the duration of the contract; such actions are called sympathy or secondary strikes. Members who honor the picket line in spite of the contract frequently face discipline, for their action may be viewed as a violation of provisions of the contract.

Therefore, any union conducting a strike action typically seeks to include a provision of amnesty for all who honored the picket line in the agreement that settles the strike. No-strike clauses may also prevent unionized workers from engaging in solidarity actions for other workers even when no picket line is crossed. For example, striking workers in manufacturing or mining produce a product which must be transported. In a situation where the factory or mine owners have replaced the strikers, unionized transport workers may feel inclined to refuse to haul any product that is produced by strikebreakers, yet their own contract obligates them to do so.

Historically the practice of union strikebreaking has been a contentious issue in the union movement, and a point of contention between adherents of different union philosophies. For example, supporters of industrial unions, which have sought to organize entire workplaces without regard to individual skills, have criticized craft unions for organizing workplaces into separate unions according to skill, a circumstance that makes union strikebreaking more common. Union strikebreaking is not unique to craft unions.

Anti-strike action

[edit]Most strikes called by unions are somewhat predictable; they typically occur after the contract has expired. However, not all strikes are called by union organizations – some strikes have been called in an effort to pressure employers to recognize unions. Other strikes may be spontaneous actions by working people. Spontaneous strikes are sometimes called "wildcat strikes"; they were the key fighting point in May 1968 in France; most commonly, they are responses to serious (often life-threatening) safety hazards in the workplace rather than wage or hour disputes, etc.

Whatever the cause of the strike, employers are generally motivated to take measures to prevent them, mitigate the impact, or to undermine strikes when they do occur.

Strike preparation

[edit]Companies which produce products for sale will frequently increase inventories prior to a strike. Salaried employees may be called upon to take the place of strikers, which may entail advance training. If the company has multiple locations, personnel may be redeployed to meet the needs of reduced staff. Companies may also take out strike insurance, to help offset the losses which a strike would cause.

When established unions commence strike action, some companies may decline entirely to negotiate with the union, and respond to the strike by hiring replacement workers. For strikers, this may be concerning for multiple reasons. For example, they may fear that the strike will be lost. The length of time that the strike may last could cause many workers to cease striking, which would likely cause it to fail. They may also be concerned that they will lose their jobs entirely. Companies that hire strikebreakers typically use these concerns to attempt to convince union members to abandon the strike and cross the union's picket line.

Unions faced with a strikebreaking situation may try to inhibit the use of strikebreakers by a variety of methods – establishing picket lines where strikebreakers enter the workplace; discouraging strike breakers from taking, or from keeping, strikebreaking jobs; raising the cost of hiring strikebreakers for the company; or employing public relations tactics. Companies may respond by increasing security forces and seeking court injunctions.

Examining conditions in the late 1990s, John Logan, professor and director of Labor and Employment Studies at San Francisco State University, observed that union busting agencies helped to "transform economic strikes into a virtually suicidal tactic for US unions". Logan further observed, "as strike rates in the United States have plummeted to historic low levels, the demand for strike management firms has also declined."[62]

In the US, as established in the National Labor Relations Act there is a legally protected right for private sector employees to strike to gain better wages, benefits, or working conditions and they cannot be fired. Striking for economic reasons (like protesting workplace conditions or supporting a union's bargaining demands) allows an employer to hire permanent replacements. The replacement worker can continue in the job and then the striking worker must wait for a vacancy.

But if the strike is due to unfair labor practices, the strikers replaced can demand immediate reinstatement when the strike ends. If a collective bargaining agreement is in effect, and it contains a "no-strike clause", a strike during the life of the contract could result in the firing of all striking employees which could result in dissolution of that union. Although this is legal it could be viewed as union busting.

Strike breaking

[edit]Some companies negotiate with the union during a strike; other companies may see a strike as an opportunity to eliminate the union. This is sometimes accomplished by the importation of replacement workers, strikebreakers or "scabs". Historically, strike breaking has often coincided with union busting. It was also called "black legging" in the early twentieth century, during the Russian socialist movement.[63]

Union busting

[edit]

One method of inhibiting or ending a strike is firing union members who are striking which can result in elimination of the union. Although this has happened, it is rare due to laws regarding firing and "right to strike" having a wide range of differences in the US depending on whether union members are public or private sector. Laws also vary country to country. In the UK, "It is important to understand that there is no right to strike in UK law."[64] Employees who strike risk dismissal, unless it is an official strike (one called or endorsed by their union) in which case they are protected from unlawful dismissal, and cannot be fired for at least 12 weeks. UK laws regarding work stoppages and strikes are defined within the Employment Relations Act 1999 and the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992.

A significant case of mass-dismissals in the UK in 2005 involved the sacking of over 600 Gate Gourmet employees at Heathrow Airport.[65] The sacking prompted a walkout by British Airways ground staff leading to cancelled flights and thousands of delayed passengers. The walkout was illegal under UK law and the T&GWU quickly brought it to an end. A subsequent court case ruled that demonstrations on a grass verge approaching the Gate Gourmet premises were not illegal, but limited the number and made the T&G responsible for their action.[66]

In 1962, US President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order #10988[67] which permitted federal employees to form trade unions but prohibited strikes (codified in 1966 at 5 U.S.C. 7311 – Loyalty and Striking). In 1981, after public sector union PATCO (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization) went on strike illegally, President Ronald Reagan fired all of the controllers. His action resulted in the dissolution of the union. PATCO reformed to become the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.

In the U.S., as established in the National Labor Relations Act there is a legally protected right for private sector employees to strike to gain better wages, benefits, or working conditions and they cannot be fired. Striking for economic reasons (i.e., protesting workplace conditions or supporting a union's bargaining demands) allows an employer to hire permanent replacements. The replacement worker can continue in the job and then the striking worker must wait for a vacancy. But if the strike is due to unfair labor practices (ULP), the strikers replaced can demand immediate reinstatement when the strike ends. If a collective bargaining agreement is in effect, and it contains a "no-strike clause", a strike during the life of the contract could result in the firing of all striking employees which could result in dissolution of that union.

Amazon has used the Law firm Wilmerhale to legally end worker strikes at its locations.[citation needed]

Lockout

[edit]Another counter to a strike is a lockout, a form of work stoppage in which an employer refuses to allow employees to work. Two of the three employers involved in the Caravan park grocery workers strike of 2003–2004 locked out their employees in response to a strike against the third member of the employer bargaining group. Lockouts are, with certain exceptions, lawful under United States labor law.

Violence

[edit]

Historically, some employers have attempted to break union strikes by force. One of the most famous examples of this occurred during the Homestead Strike of 1892. Industrialist Henry Clay Frick sent private security agents from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to break a strike, organised by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers at a Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mill. Two strikers were killed, twelve wounded, along with two Pinkertons killed and eleven wounded.

In the aftermath, Frick was shot in the neck and then stabbed by an unaffiliated anarchist, Alexander Berkman, in an assassination attempt. Frick survived the attack, while Berkman was sentenced to 22 years in prison.

Conscription

[edit]Critical infrastructure workers who are on strike may be forced back to work under military law and/or civil conscription in countries which allow conscription. In 2010, the Spanish government invoked emergency powers to conscript air traffic controllers who were on strike.[68]

Films

[edit]Non-fiction

[edit]- Final Offer – A look at the 1984 contract negotiations between General Motors and its union.

- Harlan County, USA, Director: Barbara Kopple, US 1976–A documentary film about a very long and bitter strike of coal miners in Kentucky

- American Dream, Director: Barbara Kopple, US 1990 – A documentary film about the unsuccessful 1985–1986 meatpacker's strike against Hormel Foods in Austin, Minnesota.

- Jimmy Hoffa, a labor union leader who ran the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) union from 1958 until 1971, was portrayed by Robert Blake in the 1983 TV-film Blood Feud, Trey Wilson in the 1985 television miniseries Robert Kennedy & His Times, and by Jack Nicholson in the 1992 biographical film Hoffa.

- Newsies, a Disney movie based on the Newsboys' Strike of 1899 directed by Kenny Ortega and music composed by Alan Menken.

- Bastard Boys, A miniseries based on the 1998 Australian waterfront dispute.

- Made in Dagenham, A film about the strike by female employees at the Ford Motor company in the UK.

- The Great Grunwick Strike 1976-1978 Director: Chris Thomas, Brent Trades Union Council (2007 film)

Fiction

[edit]- Statschka ("Strike"), Director: Sergei Eisenstein, Soviet Union 1924

- Brüder ("Brother"), Director: Werner Hochbaum, Germany 1929–On the general strike in the port of Hamburg, Germany in 1896/97

- The Stars Look Down, Director: Carol Reed, England 1939 – Film about a strike over safety standards at a coal mine in North-East England – based on the Cronin novel

- The Grapes of Wrath a 1940 film by John Ford includes description of migrant workers striking, and its violent breaking by employers, assisted by the police. Based on the novel by John Steinbeck.

- Salt of the Earth, Director: Herbert J. Biberman, US 1953–Fictionalized account of an actual zinc-miners' strike in Silver City, New Mexico, in which women took over the picket line to circumvent an injunction barring "striking miners" from company property. The striking women were largely played by real members of the strike, and one woman was deported to Mexico while filming. The union organizer Clinton Jencks (from Jencks v. United States fame) also participated.

- The Molly Maguires, Director: Martin Ritt, 1970 film starring Sean Connery and Richard Harris. Frustrated by the failure of strike action to achieve their industrial objectives, a secret society among Pennsylvania coal miners sabotages the mine with explosives to try to get what their industrial action failed to obtain. A Pinkerton agent infiltrates them.

- F.I.S.T., Director: Norman Jewison, 1978 – loosely based on the Teamsters union and former president Jimmy Hoffa.

- Norma Rae, Director: Martin Ritt, 1979.

- Matewan, Director: John Sayles, 1987 – critically acclaimed account of a coal mine-workers' strike and attempt to unionize in 1920 in Matewan, a small town in the hills of West Virginia.

- Made in Dagenham, 2010 – based on the strike at Fords plant in Dagenham, England, UK, which won equal pay for female workers.

Other uses

[edit]- Sometimes, "to go on strike" is used figuratively for machinery or equipment not working due to malfunction, e.g. "My computer's on strike".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ ""There is No Such Thing as an Illegal Strike": Reconceptualizing the Strike in Law and Political Economy".

- ^ Aleksander Smolar, "Towards 'Self-limiting Revolution': Poland 1970–89", in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009 Archived 25 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 127–43. This book contains accounts on certain other strike movements in other countries around the world aimed at overthrowing a regime or a foreign military presence.

- ^ Mommsen, Hans (1996). The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Translated by Forster, Elborg; Jones, Larry Eugene. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-807-82249-4.

- ^ Taylor, Tony. "Strike!". ozhistorybytes - Issue Eight: The History of Words. Archived from the original on 1 March 2006 – via hyperhistory.org.

- ^ "A body of sailors… proceeded… to Sunderland…, and at the cross there read a paper, setting forth their grievances… After this they went on board the several ships in that harbour, and struck (lowered down) their yards, in order to prevent them from proceeding to sea." (Ann. Reg. 92, 1768), quoted in Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. "strike, v.," sense 17; see also sense 24.

- ^ Worrall, Simon (1 September 2014). "Were Modern Ideas—and the American Revolution—Born on Ships at Sea?". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ François Daumas, (1969). Ägyptische Kultur im Zeitalter der Pharaonen, pp. 309. Knaur Verlag, Munich

- ^ John Romer, Ancient Lives; the story of the Pharaoh's Tombmakers. London: Phoenix Press, 1984, pp. 116–123 See also E.F. Wente, "A letter of complaint to the Vizier To", in Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 20, 1961 and W.F. Edgerton, "The strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-ninth year", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 10, 1951.

- ^ Talmud Yoma 38a

- ^ a b H.G. Wells, Outline of History, Waverly Book Company, 1920, page 225

- ^ Gault, Robert (1907). "A History of the Questionnaire Method of Research in Psychology". The Pedagogical Seminary. 14 (3): 366–383. doi:10.1080/08919402.1907.10532551.

- ^ Mather, F.C. (1974). "The General Strike of 1842: A Study in Leadership, Organisation and the Threat of Revolution during the Plug Plot Disturbance". In Quinault, R.; Stevenson, J. (eds.). Popular Protest and Public Order: Six Studies in British History, 1790–1920. George Allen & Unwin Ltd. pp. 115–140. doi:10.4324/9781003186892-3. ISBN 978-1-003-18689-2. S2CID 242636272.

- ^ "British workers strike for better wages and political reform ("The Plug Plot Riots"), 1842 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Camatte: Origin and Function of the Party Form". marxists.org.

- ^ The Poverty of Philosophy, Part II, Section 5

- ^ a b "Recognition Strike Law and Legal Definition". definitions.uslegal.com.

- ^ Adavbiele, J. A. (16 April 2015). "Implications of Incessant Strike Actions on the Implementation of Technical Education Programme in Nigeria". Journal of Education and Practice. 6 (8): 134–138. S2CID 167107092.

- ^ William R. Adams (1990). A Manager's Guide to Labor Relations Terminology. Adams, Nash & Haskell. p. 60.

- ^ a b Arensberg, Charles C. (1948–1949). "The Primary Strike for Recognition". University of Pittsburgh Law Review. 10: 137.

- ^ "The Great Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902". Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ Peterson, Florence (16 April 1938). Strikes in the United States, 1880-1936. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-403-01148-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ichniowski, Casey (1 June 1988). "Police recognition strikes: Illegal and ill-fated". Journal of Labor Research. 9 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1007/BF02685240. S2CID 54211734.

- ^ "Abbreviated Timeline of the Modern Labor Movement Archived 29 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine ", University of Wisconsin-La Crosse

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012 (2011) p 428 table 663" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2011.

- ^ Aaron Brenner; et al. (2011). The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 234–35. ISBN 978-0-7656-2645-5.

- ^ "The Best of the Texas Century—Business". Texas Monthly. 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d John Kennan, Strikes Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ Gouzoulis, Giorgos (January 2023). "What do indebted employees do? Financialisation and the decline of industrial action". Industrial Relations Journal. 54 (1): 71–94. doi:10.1111/irj.12391. hdl:1983/7ec29ae7-0441-47f7-856f-c68013308c9b. ISSN 0019-8692. S2CID 255675554.

- ^ Gouzoulis, Giorgos (25 January 2023). "Strikes: how rising household debt could slow industrial action this year". The Conversation. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b Heidi Shierholz & Margaret Poydock, Report: Continued surge in strike activity signals worker dissatisfaction with wage growth Archived 26 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Policy Institute (11 February 2020).

- ^ "Countries Compared by Labor > Strikes. International Statistics at NationMaster.com". www.nationmaster.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bruce S. Feldacker & Michael J. Hayes (2014). Labor Guide to Labor Law. Cornell University Press. pp. 231, 244–46.

- ^ "No-Strike Clauses Hold Back Unions – Labor Notes". labornotes.org. 13 December 2011.

- ^ "NATIONAL MASTER UNITED PARCEL SERVICE AGREEMENT: For The Period August 1, 2023 through July 31, 2028" (Document). International Brotherhood of Teamsters. 2023. p. 30.

It shall not be a violation of this Agreement and it shall not be cause for discharge or disciplinary action […] in the event an employee refuses to enter upon any property involved in a primary labor dispute […]

- ^ "A note from the editor – Twin Cities". 16 July 2009.

- ^ Levant, Alex. "Flying Squads and the Crisis of Workers' Self-Organization". New Socialist (40). ISSN 1488-2698. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v Saskatchewan, 2015 SCC 4

- ^ Ha-Redeye, Omar (1 February 2015). "Finding More "Meaning" in the Future of Labour Law – Slaw". Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "FAQ: Back-to-work legislation".

- ^ "Ontario judge finds back-to-work legislation aimed at postal workers violates Charter". canliiconnects.org.

- ^ "Still waiting for Nike to do it," by Tim Connor, page 70.

- ^ 'Factory to the world will soon get the right to strike' Archived 3 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News and Analysis, 26 June 2008.

- ^ Orlov V.N.; Bogdanov S.V. "КОЛЛЕКТИВНЫЕ ТРУДОВЫЕ КОНФЛИКТЫ В СССР В 1930-1950-х гг.: ПРИЧИНЫ ВОЗНИКНОВЕНИЯ, ФОРМЫ ПРОТЕКАНИЯ, СПОСОБЫ РАЗРЕШЕНИЯ" [COLLECTIVE LABOR CONFLICTS IN THE USSR IN 1930-1950s: REASONS OF OCCURRENCE, FORMS, WAYS OF RESOLUTION] (in Russian).

- ^ Réimpression de l'Ancien Moniteur (in French). Paris. 1841. p. 661.

- ^ "France: Penal Code of 1810". www.napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Legge 11 Aprile 2000, n. 83". Gazzetta Ufficiale.

- ^ a b "Police in strike action threat". BBC News. 28 July 2007.

- ^ Shawcross, Hartley (29 January 1951). "Prosecutions (Attorney-General's Responsibility)". Hansard. House of Commons Debates (c681).

- ^ Heintzman, Ralph (16 May 2020). "The real meaning of the SNC-Lavalin affair". The Globe and Mail Inc.

- ^ "Prison officers stage unofficial walkout on day of public sector action". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Prison staff strike ended after union's 'constructive dialogue' with minister". Sky News.

- ^ a b "The Court to Rule on the Right to Strike in Germany". News ECHR. 8 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "5 U.S. Code § 7311 – Loyalty and striking". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ 28 CFR 541.3

- ^ California Code of Regulations §3000,

Gang means any … formal or informal organization, association or group of three or more persons which has a common name or identifying sign or symbol whose members and/or associates, individually or collectively, engage or have engaged, on behalf of that organization, association or group, in two or more acts which include, … acts of misconduct classified as serious pursuant to section 3315.

- ^ "Inspired by West Virginia Strike, Teachers in Oklahoma and Kentucky Plan Walk Out". KTLA. 2 April 2018.

- ^ Leyton-García, Jorge-Andrés (2017). "The right to strike as a fundamental human right: recognition and limitations in international law" (PDF). Revista chilena de derecho. 44 (3): 781–804. doi:10.4067/S0718-34372017000300781.

- ^ Utz, Arthur F. (1987). "Is the Right to Strike a Human Right?". Washington University Law Review Quarterly. 65: 732–757.

- ^ Weinrib, Laura (2018). "The right to work and the right to strike". University of Chicago Legal Forum. 2017: 513–536.

- ^ Gourevitch, Alex (2018). "The Right to Strike: A Radical View". American Political Science Review. 112 (4): 905–917. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000321. S2CID 85458964.

- ^ Jennings, Karen; Western, Glenda (1997). "A Right to Strike?". Nursing Ethics. 4 (4): 277–282. doi:10.1177/096973309700400403. PMID 9305123. S2CID 40163210.

- ^ "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States", British Journal of Industrial Relations, John Logan, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, December 2006, pp. 651–675.

- ^ Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon, p. 60.

- ^ Taylor, Byron (6 June 2011). "What is the right to strike?". LabourList. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ [Workers Worldwide Back Their Heathrow Colleagues], "Internationale Transportarbeiter-Föderation: Presse". Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ [BBC News 21 August 2005], https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4168084.stm Archived 6 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Executive Order 10988,Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Spanish air traffic controllers marched back to work as airports reopen". telegraph.co.uk. 4 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Norwood, Stephen H. Strikebreaking and Intimidation. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8078-2705-3

- Montgomery, David. "Strikes in Nineteenth-Century America," Social Science History (1980) 4#1 pp. 81–104 in JSTOR, includes some comparative data

- Ross, Arthur M., and Donald Irwin."Strike Experience in Five Countries, 1927-1947: An Interpretation" ILR Review 4#3 (1951), pp. 323–342 online, covers UK, USA, Canada, Australia and Sweden.

- Silver, Beverly J. Forces of Labor: Workers' Movements and Globalization Since 1870. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-52077-0

External links

[edit]- Reconceptualizing the strike in law and political economy

- News and histories of strikes from around the world

- "Black Workers and the Labor Movement: Toward a Paradigm of Unity in Afro-American Studies." Intro to Afro-American Studies. eBlackStudies.com. Archived 8 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Labour Law Profile: Ireland

- Strike! Famous Worker Uprisings Archived 18 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life