Isle of Dogs

| Isle of Dogs | |

|---|---|

Location of the Isle of Dogs within Inner London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ375785 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | E14 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

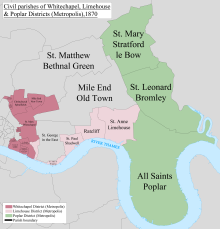

The Isle of Dogs is a large peninsula bounded on three sides by a large meander in the River Thames in East London, England. It includes the Cubitt Town, Millwall and Canary Wharf districts. The area was historically part of the Manor, Hamlet, Parish and, for a time, the wider borough of Poplar. The name had no official status until the 1987 creation of the Isle of Dogs Neighbourhood by Tower Hamlets London Borough Council. It has been known locally as simply "the Island" since the 19th century.[1]

The whole area was once known as Stepney Marsh; Anton van den Wyngaerde's "Panorama of London" dated 1543 depicts and refers to the Isle of Dogs. Records show that ships preparing to carry the English royal household to Calais in 1520 docked at the southern bank of the island. The name Isle of Dogges occurs in the Thamesis Descriptio of 1588, applied to a small island in the south-western part of the peninsula. The name is next applied to the Isle of Dogs Farm (originally known as Pomfret Manor) shown on a map of 1683. At the same time, the area was variously known as Isle of Dogs or the Blackwell levels. By 1855, it was incorporated within the parish of Poplar under the aegis of the Poplar Board of Works. This was incorporated into the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar on its formation in 1900.[1]

Geology

[edit]The soil is alluvial and silty in nature, underlaid by clay or mud, with a peat layer in places.[1]

Etymology and heraldry

[edit]The first known written mention of the Isle of Dogs is in the Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII. In Volume 3, entry 1009 "Shipping" dated 2 October 1520, there is a list of purchases, which includes "A hose for the Mary George, in dock at the Isle of Dogs, 10d."[2]

The 1898 edition of Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable attributes the name: "So called from being the receptacle of the greyhounds of Edward III. Some say it is a corruption of the Isle of Ducks, and that it is so called in ancient records from the number of wild fowl inhabiting the marshes."[3] Other sources[1][4] discount this, believing these stories to all derive from the antiquarian John Strype, and believe it might come from one of the following:

- a nickname of contempt: Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe wrote a satirical play in 1597, which was a mocking attack on the island of Great Britain, titled The Isle of Dogs, which offended some in the nobility. Jonson was imprisoned for a year; Nashe avoided arrest by fleeing the area. Samuel Pepys referred to the "unlucky Isle of Doggs."[5]

- the presence of Dutch engineers reclaiming the land from a disastrous flood.[1]

- the presence of gibbets on the foreshore facing Greenwich.[1]

- a yeoman farmer called Brache, this being an old word for a type of hunting dog.[1]

- the dogs of a later king, Henry VIII, who also kept deer in Greenwich Park. Again it is thought that his hunting dogs might have been kept in derelict farm buildings on the island. Now known as the area West Ferry Circus.[1][6]

- Isle of Dykes, which then got corrupted over the years.[7]

Laura Wright in a 2015 essay showed that in the Elizabethan era the term "Isle of Dogges" was applied to a small eyot (mud island)[8] lying offshore the present-day Isle of Dogs. It was across the river from the royal Deptford dockyard, whose vessels being outfitted were moored at the eyot; the first record of the name appears about the time the dockyard was established. The peninsula itself at that time was always known as Stepney Marsh. A government map, prepared in connection with the Thames defences at the time of the Spanish Armada, suggests the eyot was a recognised navigational landmark alongside an otherwise featureless marsh. Later, the name was extended to a farm on the peninsula, and then to the peninsula itself. That the name referred to the site of royal kennels, she argued, was unsupported speculation 200 years after the first attested usage.[9] Dr Wright offered a speculation of her own: that the name "dogs" was bestowed by the Deptford dockyard workers as a punning reference to the barks (naval vessels) moored at this eyot.

The lost Ben Jonson/Thomas Nashe play (above) was vigorously pursued by the authorities, who even employed a torturer to track down its authors. "The severity of the response seems too great to have been triggered by an attack on a mere individual"; it has been hypothesised that what the play satirised was the then appalling state of England's defences, the play's title Isle of Dogs being taken to mean the place where the Queen's ships were outfitted.[9]: 106–112

It is said that Canary Wharf, located in the Isle of Dogs, took its name from sea trade with the Canary Islands, which were named in Latin as Canariae Insulae (lit. 'Dog Islands'). However the name Canary Wharf does not appear until 1936.[9]: 89–90

The Talbot dog in the coat of arms of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets represents the Isle of Dogs.[10]

Society

[edit]

Following the building of the Docks (especially the West India Docks and the adjacent City Canal), and with an increasing population, locals increasingly referred to the area as The Island. This area includes Millwall, Cubitt Town, and Blackwall. The south of the isle opposite Greenwich was once known as North Greenwich, now applied to the area around the Millennium Dome on the Greenwich Peninsula. Between 1986 and 1992 it enjoyed a brief formal existence, as the name Isle of Dogs was applied to one of seven neighbourhoods to which power was devolved from the council. The neighbourhood was later abolished.[11]

It was the site of the highest concentration of council housing in England but is now best known as the location of the Canary Wharf office complex. One Canada Square, also known as the Canary Wharf Tower, is the second tallest habitable building in Britain at 244 metres (801 ft).[12] The peninsula is an area of social extremes, comprising some of the most prosperous and most deprived areas of the country; in 2004, nearby Blackwall was the 81st most deprived ward in England out of over 8,000,[13] while the presence of Canary Wharf gives the area one of the highest average incomes in the UK.[14] Lincoln Plaza was the 2016 winner of the Carbuncle Cup for the year's "worst new building" and The Times described it as "mediocre at best, ugly at worst".[15]

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]The Isle of Dogs is situated some distance downriver from the City of London. It was originally marsh, being several feet below water at high tide. In the Middle Ages it was made available for human habitation by a process known in the Thames estuary as inning. The reclaimed land was below high water, protected by earthen banks.[16] These banks if not properly kept up were liable to be breached. This happened in 1448, drowning the land for 40 years.[17]

In 1660, the river started to break through the neck of the peninsula, initiating meander cutoff. This was arrested by human intervention, but it left a 5-acre lake called Poplar Gut. It appears on John Rocque's 1746 Map of London and ten miles around, in the extract reproduced in this article.

One road led across the Marshes to an ancient ferry, at Ferry Road. There was rich grazing on the marsh, and cattle were slaughtered in fields known as the Killing Fields, south of Poplar High Street.[citation needed]

The western side of the island was known as Marsh Wall, and the district became known as Millwall with the building of the docks, and from the number of windmills constructed along the top of the flood defence.[citation needed]

Industry

[edit]

In 1802, the West India Docks began to be developed on the Isle of Dogs. Beginning in 1812 the Poplar and Greenwich Ferry Roads Company installed tolls on the East Ferry Road. These proved to be unpopular and after many years of lobbying the Metropolitan Board of Works bought the company and abolished the tolls in 1885.[18]

The Docks brought with them many associated industries, such as flour and sugar processing, and also ship building. On 31 January 1858 the largest ship of that time, the SS Great Eastern designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was launched from the yard of Messrs Scott, Russell & Co, of Millwall.[citation needed] The 211 metres (692 ft) length was too big for the river so the ship had to be launched sideways. Due to the technical difficulties of the launch this was the last big ship to be built on the Island and the industry fell into a decline. However, parts of the launching slipway and plate works have been preserved in situ and may be seen close to Masthouse Terrace Pier.[citation needed]

Docks

[edit]

The urbanisation of the Isle of Dogs took place in the 19th century following the construction of the West India Docks, which opened in 1802. This heralded the area's most successful period, when it became an important centre for trade. The East India Docks were subsequently opened in 1806, followed by Millwall Dock in 1868.

By the 1880s, the casual employment system caused Dock workers to unionise under Ben Tillett and John Burns.[19] This led to a demand for 6d per hour (2.5p), and an end to casual labour in the docks. After a bitter struggle, the London Dock Strike of 1889 was settled with victory for the strikers, and established a national movement for the unionisation of casual workers.

The three dock systems were unified in 1909 when the Port of London Authority took control of the docks. With the docks stretching across from East to West with locks at each end, the Isle of Dogs could now almost be described as a genuine island.

Dock workers settled on the "island" as the docks grew in importance, and by 1901, 21,000 people lived there, largely dependent on the river trade on the Isle as well as in Greenwich and Deptford across the river to the south and west. The Isle of Dogs was connected to the rest of London by the London and Blackwall Railway, opened in 1840 and progressively extended thereafter. In 1902, the ferry to Greenwich was replaced by the construction of the Greenwich foot tunnel, and Island Gardens park was laid out in 1895, providing views across the river. The London and Blackwall Railway closed in 1926. Until the building of the Docklands Light Railway in 1987, the only public transport accessing and exiting the Island consisted of buses using its perimeter roads. These were frequently and substantially delayed by the movement of up to four bridges which allowed ships access to the West India Docks and Millwall Docks. The insular nature of the Island caused its separateness from the rest of London, and its unique nature.

During World War II, the docks were a key target for the German Luftwaffe and were heavily bombed. A number of local civilians were killed in the bombing and extensive destruction was caused on the ground, with many warehouses being destroyed and much of the dock system being put out of action for an extended period. Unexploded bombs from this period continue to be discovered today.[20] Anti-aircraft batteries were based on Mudchute Farm; their concrete bases remain today.[21]

After the war, the docks underwent a brief resurgence and were even upgraded in 1967. However, with the advent of containerisation, which the docks could not handle, they became obsolete soon afterwards. The docks closed progressively during the 1970s, with the last – the West India and Millwall docks – closing down in 1980. This left the area in a severely dilapidated state, with large areas being derelict and abandoned.

'Unilateral declaration of independence'

[edit]Local residents resented the scarcity of schools and supermarkets and inadequate transport to neighbourhoods that did have them.[22][23] On 1 March 1970 a group of activists led by Ted John and John Westfallen, in a reference to the Republic of Rhodesia's recent unilateral declaration of independence or UDI,[24] issued a UDI for the Isle of Dogs. For two hours[24][25] (though some reports say a day,[26] others a week[22]) they blocked the two swing-bridges providing the only access to the area by road.[24] According to Johns the intent was semi-jocular [24] and the purpose was only to achieve independence from the rest of London,[23] a right already enjoyed by the nearby City: it was the Press who dubbed him "President Ted of the Isle of Dogs'.[27] Nevertheless, and though a body of local opinion resented the stunt,[28][29] it achieved wide national and international publicity. It featured on the front page of the New York Times,[23] and Johns was interviewed by satellite by Walter Cronkite for CBS Evening News.[24] A new secondary school and improvements in public transport materialised.[27] According to one source it even served as the catalyst for the eventual development of Canary Wharf.[24]

Patricia Cornwell's 2002 novel Isle of Dogs features an island off the coast of Virginia that declares UDI, "claiming its independence lies with those who set sail from the Isle of Dogs in 1607".[30]

London Docklands Development Corporation

[edit]Successive Labour and Conservative governments proposed a number of action plans during the 1970s but it was not until 1981 that the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was established to redevelop the area. The Isle of Dogs became part of an enterprise zone, which covered 1.95 km2 of land and encompassed the West India, Millwall and East India Docks. New housing, office space and transport infrastructure were built. This included the Docklands Light Railway and later the Jubilee line extension, which eventually brought access to the London Underground to the area for the first time.

Since its construction in 1987–1991, the area has been dominated by the expanding Canary Wharf development with over 437,000 square metres (4,700,000 sq ft) of office and retail space having been created; 93,000 now work in Canary Wharf alone.[31]

Politics

[edit]The Island achieved notoriety in 1993 when Derek Beackon of the British National Party became a councillor for Millwall ward, in a by-election. This was the culmination of years when race was a prominent issue in local politics, especially with regards to allocation of housing.[32] Labour regained the ward in the full council election of May 1994, and held all three seats until a further by-election in September 2004.

Incidents

[edit]On 9 February 1996, the IRA detonated a truck bomb near South Quay DLR station on the Isle of Dogs that killed two people and injured more than a hundred others.[33]

Education

[edit]There are four state primary schools located on the Isle of Dogs – Cubitt Town Junior School, Arnhem Wharf, Harbinger School and St Edmunds. There was also an independent primary school, River House Montessori,[34] located near South Quay, but this closed in 2024.

George Green's School is a secondary school and Specialist Humanities School at the southern tip of the island.

Canary Wharf College[35] is a free school on the Island which covers primary and secondary education.[36]

Transport

[edit]London Underground, DLR, and Elizabeth line stations

[edit]The nearest London Underground station is Canary Wharf on the Jubilee line. Key areas including Regent's Park, The West End, Westminster, South Bank, Millennium Dome and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, are all within 20 minutes of Canary Wharf by Tube.

The DLR runs north–south through the Isle of Dogs. DLR stations are Canary Wharf, Heron Quays, South Quay, Crossharbour, Mudchute and Island Gardens. Key areas including the City of London, Tower Hill and Greenwich are all within 20 minutes of the Isle of Dogs by DLR.

The Elizabeth line's Canary Wharf station opened in 2022. Situated at the north of the Island, it provides high-frequency, fast connections to the heart of the West End, Paddington Station, Heathrow Airport and Abbey Wood.

London bus routes

[edit]- London Buses route 135

- London Buses route 277

- London Buses route D3

- London Buses route D6

- London Buses route D7

- London Buses route D8

- London Buses route N550

River bus services

[edit]Regular commuter boat services serve both Masthouse Terrace Pier and Canary Wharf Pier on the Isle of Dogs.

The Thames Clippers provides regular commuter services to Woolwich Arsenal Pier, Greenwich Pier in the east, and the City of London including St. Katherine Docks, Tower Bridge, HMS Belfast, Greater London Authority building, Tate Modern, Blackfriars, as well as the West End of London in the west on the commuter service. There is also a connecting shuttle service to Rotherhithe and the Tate to Tate service from Tate Modern to Tate Britain via London Eye.

From Summer 2007, the service has been enhanced with express boats[37] from central London to the O2 Arena (former Millennium Dome).

Pedestrian and cyclists

[edit]The Thames Path National Trail runs along the riverside. At the southern end of the Isle of Dogs, the Greenwich foot tunnel provides pedestrian access to Greenwich, across the river.

National Cycle Network route 1 runs through the foot tunnel (although cycles must not be ridden in the tunnel itself).

Airport and helipad

[edit]The nearest airport is London City Airport, which is 25 minutes away from Canary Wharf by DLR.

There is also a helipad situated on the west of the Island and next to Ferguson's Wharf, which is privately run by Vanguard.[38]

Sailing and watersports activities

[edit]The presence of docks, some of a considerable size, has enabled a practice of various watersports, like sailing, kayaking, windsurfing and standup paddleboarding.

Docklands Sailing and Watersports Centre[39] is one of the main reference spots for watersports fans.

The Duchess of Cambridge visited the centre in 2017.[40]

In the media

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land contains the lines "The barges wash / Drifting logs / Down Greenwich reach / Past the Isle of Dogs."[41]

In modern times the Isle of Dogs has provided locations for many blockbuster films, including the opening scenes of the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough, and more recently Batman Begins, The Constant Gardener, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, and Love Actually. The Isle of Dogs featured heavily in the 1980 British film The Long Good Friday,[42] and the Isle of Dogs is the primary location of the 2007 horror film 28 Weeks Later, where it is the only secure and quarantined area in all of Britain suitable for recivilisation after a virus epidemic kills the population of Britain.

The Isle of Dogs was the setting for the 1986 Channel 4 comedy-drama Prospects starring Gary Olsen and Brian Bovell.

While shooting in East London for his film Fantastic Mr. Fox, Wes Anderson spotted a road sign directing to the Isle of Dogs. This sparked his imagination, becoming an eponymous source of inspiration for his animated 2018 film Isle of Dogs.[43]

See also

[edit]- Burrells Wharf

- Crossrail

- Honourable East India Company

- Island History Trust

- Islands in the River Thames

- London Museum Docklands

- Samuda Estate

- SS Robin

References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h The Isle of Dogs: Introduction, Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 375-87 accessed: 9 February 2007

- ^ "Henry VIII: October 1520", in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 3, 1519–1523, ed. J. S. Brewer (London, 1867), British History Online. pp. 372. Accessed 11 December 2024.

- ^ "E. Cobham Brewer 1810–1897. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. (1898)". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Tower Hamlets website Archived 29 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pepys, Samuel (1 January 1971), Latham, Robert; Matthews, William (eds.), "The Diary", The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Vol. 1: 1660, Harper Collins (UK); University of California Press (US), doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00174762, ISBN 9780004990217, retrieved 22 February 2023

- ^ "An Account of the Hamlet of Poplar, in Middlesex". The Universal magazine. East London History Society. June 1795. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

It is opposite Greenwich in Kent; and when our sovereigns had a palace near the site of the present magnificent hospital, they used it as a hunting-seat, and, it is said, kept the kennels of their hounds in this marsh. These hounds frequently making a great noise, the seamen called the place the Isle of Dogs.

- ^ The Isle of Dogs and Docklands. Archived 31 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The eyot may have formed a pair of islands at high tide.

- ^ a b c Wright, Laura (2005). "On the Place-Name Isle of Dogs". In Shaw, Philip; Erman, Britt; Melchers, Gunnel; Sundkvistsher, Peter (eds.). From Clerks to Corpora: Essays on the English Language Yesterday and Today. Stockholm University Press. doi:10.16993/sup.bab. ISBN 978-91-7635-006-5. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Heraldry of the world https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/heraldrywiki/index.php?title=Tower_Hamlets

- ^ Tower Hamlets Borough Council Election Maps 1964-2002 Archived 4 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine accessed: 9 February 2007

- ^ "Welcome to the Canary Wharf Group plc website". Archived from the original on 5 April 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Isle of Dogs Community Foundation report August 2004 indicates that Blackwall was in the most deprived 1% of wards Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ward Data Report Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Theme 3: Creating & sharing prosperity (Tower Hamlets Partnership, 2004) accessed 2 May 2008

- ^ Jonathan Morrison (1 July 2017). "There are ways to build homes that people want to live in". The Times. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Hobhouse, Hermione, ed. (1994). "The Isle of Dogs: Introduction". Survey of London: Volumes 43 and 44, Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. London: British History Online.

- ^ Croot, Patricia (1997). "Settlement, Tenure and Land Use in Medieval Stepney: Evidence of a Field Survey c. 1400". The London Journal. 22 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1179/ldn.1997.22.1.1.

- ^ Island History (13 January 2020). "East Ferry Road – The Oldest Road on the Isle of Dogs". Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ John Burns is commemorated in the name given to a current Woolwich Ferry

- ^ "World War II bomb found at Canary Wharf". BBC News. 28 July 2007.

- ^ "Mudchute in WWII". Mudchute Park & Farm. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ a b Mason, John (12 May 2004). "Obituary: Ted Johns". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Weinraub, Bernard (10 March 1970). "Dock Area in London Declares Its 'Independence'". New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Lemmerman, Mick (7 December 2013). "'It was all a bit of a joke' - the Isle of Dogs' unilateral declaration of independence". Isle of Dogs - Past Life, Past Lives: Two Hundred Years of Docks, Industry & Islanders. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ Ted Johns The Daily Telegraph (London). 14 May 2004.

- ^ Brooke, Mike (2 October 2017). "Even Thames Armada and sheep couldn't stop Docklands invasion of Isle of Dogs". East London Advertiser. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Harker, Joseph (11 February 1994). "Notes & Queries". The Guardian. London. p. A4.

- ^ Foster, Janet (1998). Docklands: Cultures in Conflict, Worlds in Collision. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1857282733. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "A Very Strange Day in British History – The London Island that Declared Independence". ITN Archive. 1970. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Isle of Dogs". Hampshire County Council Library Service. Retrieved 6 January 2025.,

- ^ Welcome to the Canary Wharf Group plc website Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Copsey, Nigel (2004). Contemporary British Fascism: The British National Party and its Quest for Legitimacy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 52–64. ISBN 978-1-4039-0214-6.

- ^ Cusick, James (11 February 1996). "80 Minutes: The Timetable of Terror". The Independent. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Welcome to River House Montessori School". River House Primary School. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Canary Wharf College". canarywharfcollege.co.uk. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Canary Wharf College 3 - GOV.UK". Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "Travelling to The O2". ThamesClippers. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "Welcome to Vanguard Helipad". vanguardhelipad.co.uk. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Docklands Sailing and Watersports Centre". dscw.org. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Duchess of Cambridge meets pupils during docklands sailing and watersports centre visit". eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/duchess-of-cambridge-meets-pupils-during-docklands-sailing-and-watersports-centre-visit-1-5065357. 16 June 2017. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "The Waste Land", Project Gutenberg, retrieved 2 April 2018

- ^ "Five Best Film Scenes Set On The Thames", Thames Leisure, 11 May 2016, retrieved 20 June 2016

- ^ Rozanne Els (22 June 2018). "Wes Anderson says a road sign in East London was the real-life inspiration behind Isle of Dogs". Channel24.co.za. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Eve Hostettler, The Isle of Dogs: 1066–1918: A Brief History, Volume I (London: Island History Trust, 2000) ISBN 0-9508815-4-6

- Eve Hostettler, The Isle of Dogs: The Twentieth Century: A Brief History, Volume II (London: Island History Trust, 2001) ISBN 0-9508815-5-4

- Mick Lemmerman, The Isle of Dogs During World War II (Amazon, 2015) ISBN 978-1-5077-4611-0

- Mike Seaborne, The Isle of Dogs - Before The Big Money London: Hoxton Mini Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-9105-6639-8

- Con Maloney, Boozers, Bompers & Bridgers - The History of the Public Houses of the Isle of Dogs (London: Friends of Island History Trust, 2020) ISBN 978-1-5272-8827-0

- Ann Regan-Atherton, Heavy Rescue Work on the Isle of Dogs (Amazon, 2015) ISBN 978-1-5196-1086-7

External links

[edit]- Island Heritage & History Trust (archived 24 January 2001)

- Isle of Dogs landscape architecture (archived 17 October 2007)